Industrialisation 1860s Onwards

Processes Procuring Pressing Fermentation Blending Packaging Distribution The Work Force The Amount Made

Herefordshire Cider Take Overs List of Cider Makers 1953

Firms in the Area Parry Godwins Ridlers Evans Westons Bonner and Durrant Watkins Yeomans Bulmers Symonds

When Did Factory Cider Begin

The whole ethos of factory cider making was about expanding the business, this is what drove the managers and owners. Curiously this attitude didn’t reach cider until the late 19th century.

Before the late 19th century cider was made on a small scale in the farm house. The Cider Museum has an excellent display showing this timeless process. Though it was basically a cottage industry this system was capable of producing quite large quantities. It is estimated that in the early 19th century the four West Midland counties produced 15,000 hogsheads a year (a hogshead is 64 gallons, though in Herefordshire it can mean 100 gallons), over a million gallons, for sale to dealers and as much again for their own consumption. One of the people we interviewed for the Apples and Pears project, Tom Nichols, told us that even in the early 1940s his farm made three or four hogsheads of cider of 100 gallons and four or five sixty gallon ones a year, in the old fashioned way. Mashing and pressing the fruit in the cider house, fermenting and storing it in wooden barrels. The cider was drunk by the family and by men working on the farm. People came by in the evening to drink as well, using the farm kitchen as a sort of informal pub.

Settle at Black Hall Farm, people used to drop by and drink cider

Cider continues to be made in this way on some Herefordshire farms right up to today, but in the late 19th century factory made cider began as well.

Like other businesses, factory cider had three aims, to increase output, reduce costs and somehow stave off the competition sufficiently to maintain the selling price. With cider this was achieved by stimulating demand through marketing, reducing costs through mechanisation and production lines and maintaining price through take-overs.

The factory model was and is very successful, but not totally so. Large means unadaptable, not able to cater for specialist products. Bulmers for example, the biggest producer, used to make perry but because the local crop of pears is small and unreliable it became unprofitable to make. This leaves the market open for the smaller, specialist producer. Big also means you have huge running costs, if something goes wrong and the cider isn’t selling, costs mount up stupendously.

In Herefordshire factory cider began quite late, around the 1880s with Bulmers (from 1887), Godwins (1898) Westons (from 1880), Ridlers of Clehonger (1870), Symonds of Stock Lacy, and Evans of Widemarsh Common (1850 on a small scale, 1880s factory cider). At least twelve factories were working in Herefordshire at this time. Why did it take so long for factory cider to take off? Railways had something to do with it, they made it possible to distribute cider while it was fresh and at its best. This was particularly the case in Herefordshire. In the 1880s and for about forty years railways reached every corner of the county and carried all manner of heavy goods into the cities.

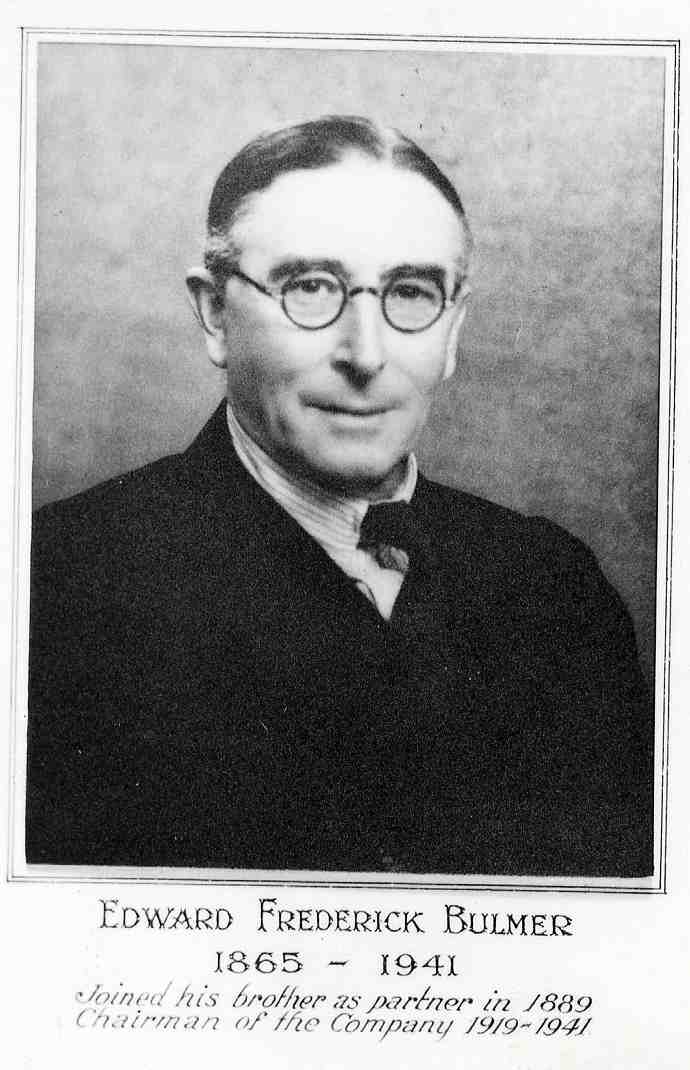

Another reason was the attitude of a few ambitious young men who emerged at this time. In 1887 the only difference between the Bulmer’s ‘factory’ and farmhouse cider produced elsewhere in the county was that Percy and Fred Bulmer were determined to make a business of it. They could see that there was money to be made, that the trade was undeveloped and therefore full of potential. The brothers borrowed money and worked round the clock, developing markets, inventing machines and expanding production.

The appeal of cider then was much the same as today, it was cheap, apple trees grew on most farms needing little attention, it had a healthful image, and country people were accustomed to it. Then as now cider production was very much dependent on weather. Hot weather stimulated demand, cold weather depressed it and failed apple crops gave problems of supply.

Top of PageFrom the earliest days the cider business had to incorporate all aspects, making, marketing, packaging, delivering, procuring and even growing apples, all these parts had to be working for a successful business. In the factory cider making was divided into the departments of procuring, production, bottling, packaging and delivery, plus the support staff such as engineers, clerks, canteen staff and the like. Pressing, bottling and packaging were done by employees working in teams and on production lines.

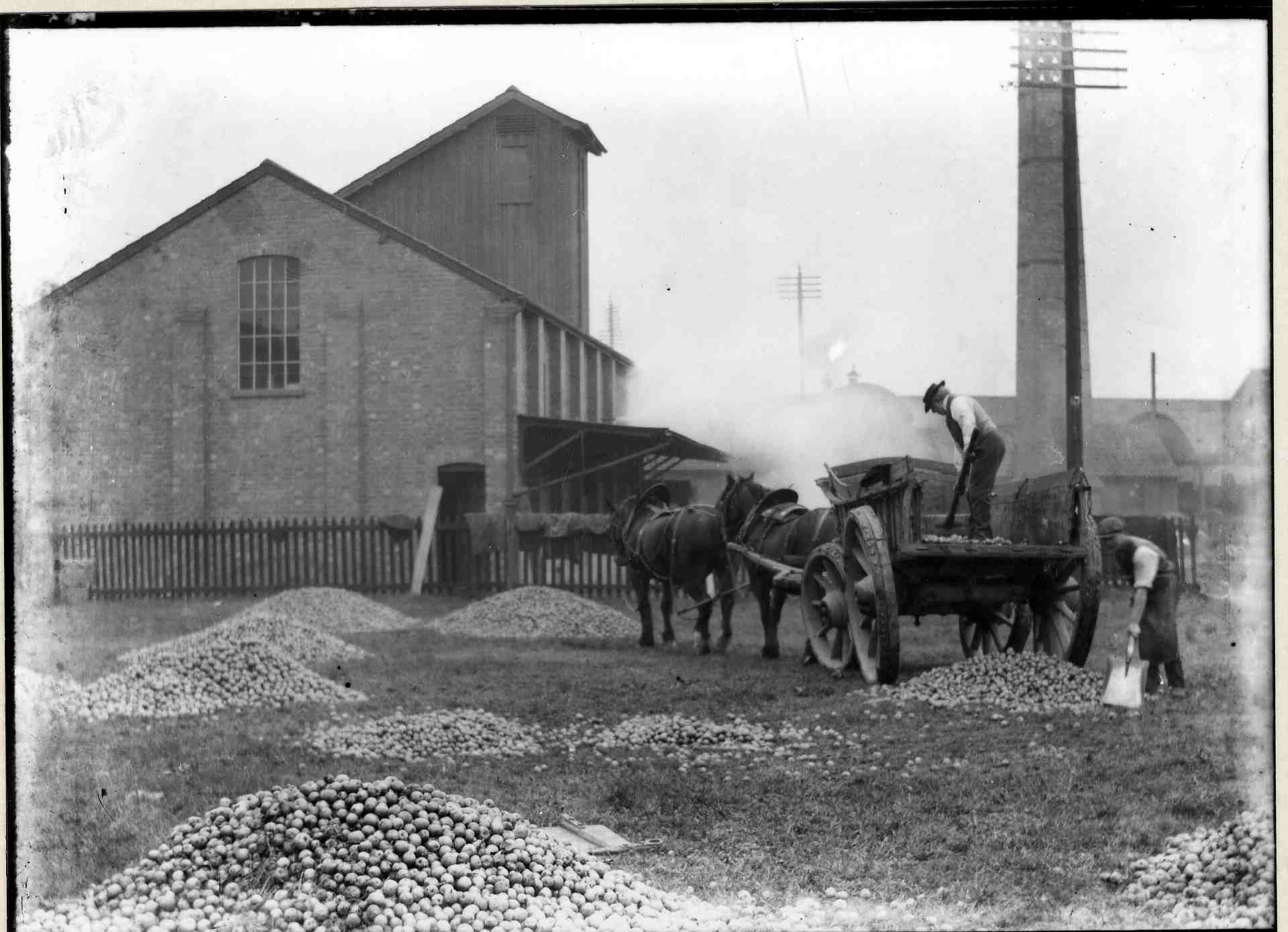

From the first until the present day apples were brought into the factories from the surrounding farms. All manner of loads and apples were delivered.

"If you had an apple tree in your back garden, we’d buy the apples. We used to have probably 2000 suppliers or something like that. Ridiculous! And they were coming in, in the boots of cars, a couple of sacks and a little trailer on, all that sort of thing. Most of it when I first started, well 90% of it when it came in was all in sacks and bags, was all man-handled in. That suddenly changed over to bulk deliveries and of course we had to alter all the canal reception areas then into tipping areas and conveyors, and all that had to change.

Cedric Olive, Bulmers

Delivering apples

"From September October when the fruit started coming in they needed staff to see to all the permits. … At the end of August they would send out cards asking farmers how much fruit they wanted to sell. After that, when it was ripe, they would phone through and that’s when I came in. I was told ‘get their name, how much they want to bring in and get off’, as fast as that, onto the next one. The phone was on all the time. They had old plates, to thump out the permit. Some permits were sent out, but if they wanted them that day they would call for it. You could only take so much in, once you’d reach that, that day was full. We would have to say ‘I’m sorry we can’t.’ Though when it was little bits and you knew them, sometimes you could take it. Two big dealers, H Weavers and G Weavers, started tippers. They would say I want ten ton every week, or two tons every day, and they would give that in, in plenty of time."

Margueritte Fellows, Fruit Office Bulmers, 1970-1990

As Margueritte says some farmers took their apples to a merchant who would buy them at a guaranteed price and then sell them onto the factory.

"Hereward Weaver was one of the founder member of what was then G Weaver and Sons. Hereward’s father, G Weaver, took the very first load of apples into Bulmers in 1932. It was an old Ford K lorry taking one and a half tons. The lorry was new in this area, where there is a very steep bank going up towards Hollybush, Hereward’s father jumped out and said, ‘I’ll have to walk it’ (today Weaver lorries carry 20 to 30 tons). In the past there was no bulk transport, no loading shovels, everything had to be done by hand. In the 1950s and 1960s we had ten to 15 men working because everything had to be loaded by hand, somebody on the bottom gave a sack to someone on the lorry and so on."

Mary Weaver

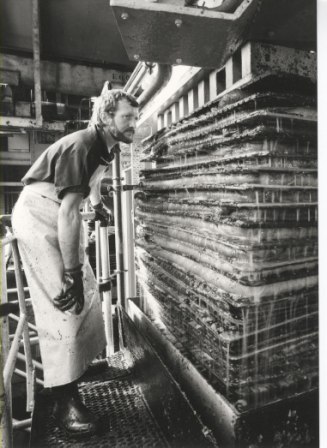

Even in the factories pressing was done in the traditional way using cheese bed presses. These were used right up until the late 1970s in Bulmers, and as late as 2000 at Westons.

"I started pressing, it was hard work, very cold in the winter like, as it got more mechanised so the job got a bit easier, they got more men, you started to move up the ladder a bit, get a bit higher, in the end you were doing next to nothing."

Ben Emmett, Bulmers

"Just after the second world war during cider making times you would have a queue of men looking for work, whoever was in charge would walk out and say I’ll have you, you, you and you and it was done on a daily basis and they’d get paid at the end of a shift."

Frank Whitcomb, Bulmers

At Bulmers from the 1960s the pressing was done by Irish labour, local people would no longer do it, it was too hard work. About one hundred Irish would come over every year between September and December and work twelve hour shifts day and night. They did this until the machinery changed, the job got easier, and they were no longer needed.

"In the early days the cheeses were of hessian, that was hard work with those. You can imagine when it was soaked with cider and pulp and whatever, you’d need a team of horses to move them, yet only two men would do it. … the two blokes on the press, it was no good them standing there scratching their nose, they had to get on and do it, because otherwise, here it (the apple pulp) came again boys. It was a production line, but they did have a switch, they could knock it off. But if the mill supervisor came round and saw them hit it, he’d come over and say ‘what you do that for’. They had to keep it going, if Farmers Jones is coming in bringing another 20 tonnes of apples in, its no good having them rotting in the canal, you’ve got to get them through."

Frank Whitcomb, Bulmers

"With the old presses it was very, very manual , physical work, heavy work. The later racking presses were hydraulic. It was just the same old fashioned way, you had the rams on the presses going up and down and that was basic for years and years right back to the farm days … The old bed presses were 3 Stage Tange presses. They proved to be not good enough for the job, they were breaking down too much, they were replaced with Buchers and Rosedown presses. They remained with that type of press for the next 20 years and then the modification of the mill began where you got the new belt presses and the Bucher presses started to come in and then the evaporator in ’95 came in – the first evaporator – then the ’98 evaporator came in and that’s where it is now.

Cedric Olive, Chief Cider Maker, Bulmers

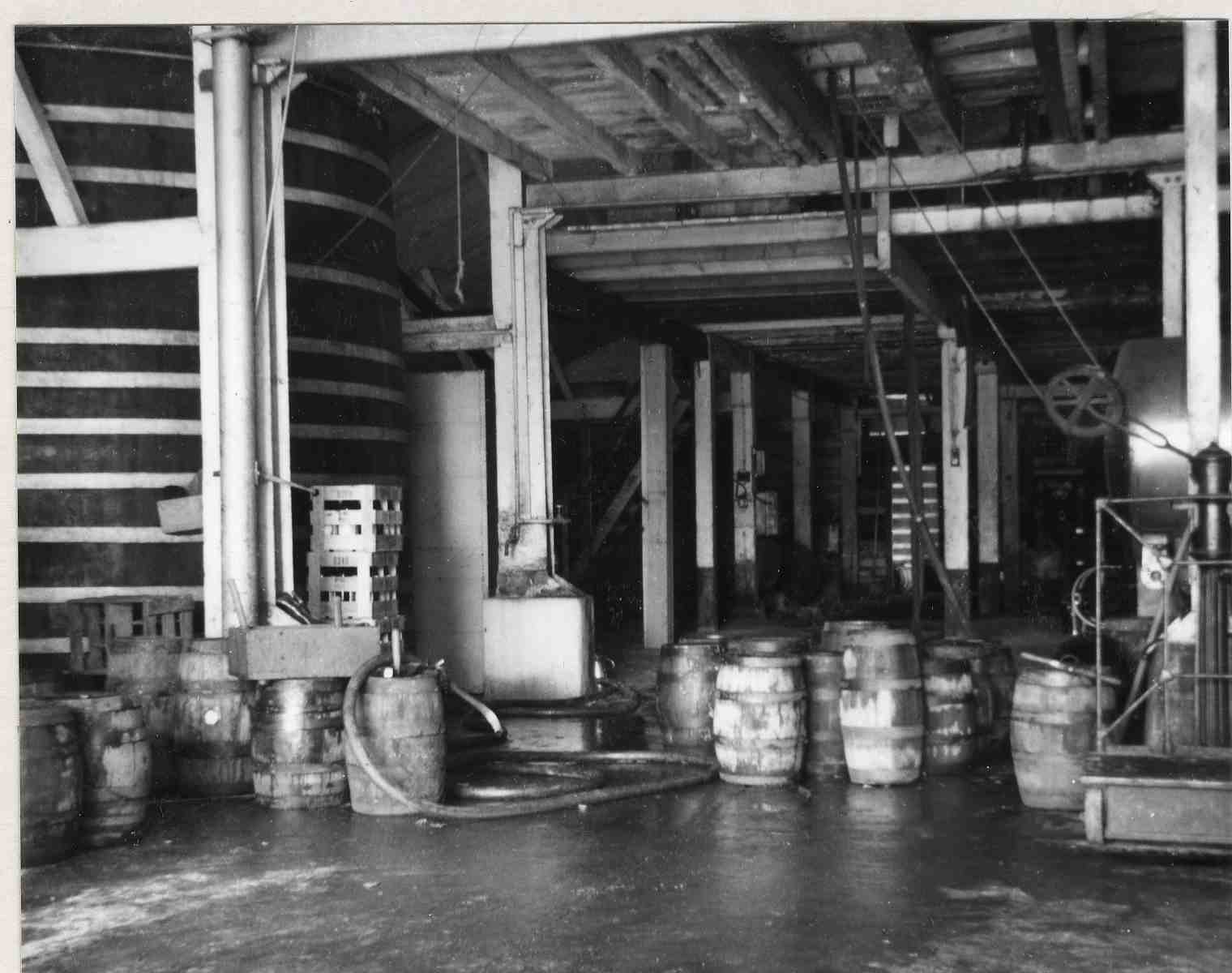

The fermentation was carried out in huge wooden barrels. The ones on display in the cider museum, though they look enormous to the unaccustomed eye are actually quite small. Bulmers and Westons vats are far bigger.

"We had one or two that were very, very small, 3000 gallons, but they were not big enough to do anything with. Even for making up the yeast pitch to go into Strongbow, I’d make 20,000 gallons of yeast and add it to 60,000 of concentrate and water to it."

Frank Whitcomb, Bulmers

In 1904 Bulmers experimented with making large 10,000 gallon oak vats. These worked and later they were able to make 50,000 and 60,000 oak vats. In recent years Bulmers have gone largely over to steel tanks including the famous Strongbow vat which at 1.6 million gallons is the largest vessel for storage of alcoholic liquor in the world. In many cider factories however the barrels are still of oak. Looking after the barrels was part of the factory work.

"One barrel called Evesham, was 20,000 gallons, it never got filled to the top as it was a specialist product, so the top dried out and virtually rotted. We had a couple of guys in those days, Eddie Strangwood and Geoff Field. Eddie was by profession a wheelwright and Geoff was a carpenter, and between them they cut the head out of this vat and put the head back in and reband it. That’s a coopers job, and you wouldn’t have known it had been done. They splice the uprights to join them, cut a diagonal. They don’t bind them, it’s just the weight holds them together. We used to buy vat rush from East Anglia. If there was a leak nine times out of ten, all you did was get a hammer and belt the band down. It this didn’t work you get this vat rush into the seam and tap it in with a chisel all the way down. Mickie Munford used to look after the vats, the taps and everything. The outside was treated with linseed oil, the only thing that touched the inside was water to clean it and cider. I’ve got a piece of oak from a vat, you can see that the linseed has only gone into the oak about 2mm the cider the same way, the actual oak is white."

Frank Whitcomb, Bulmers

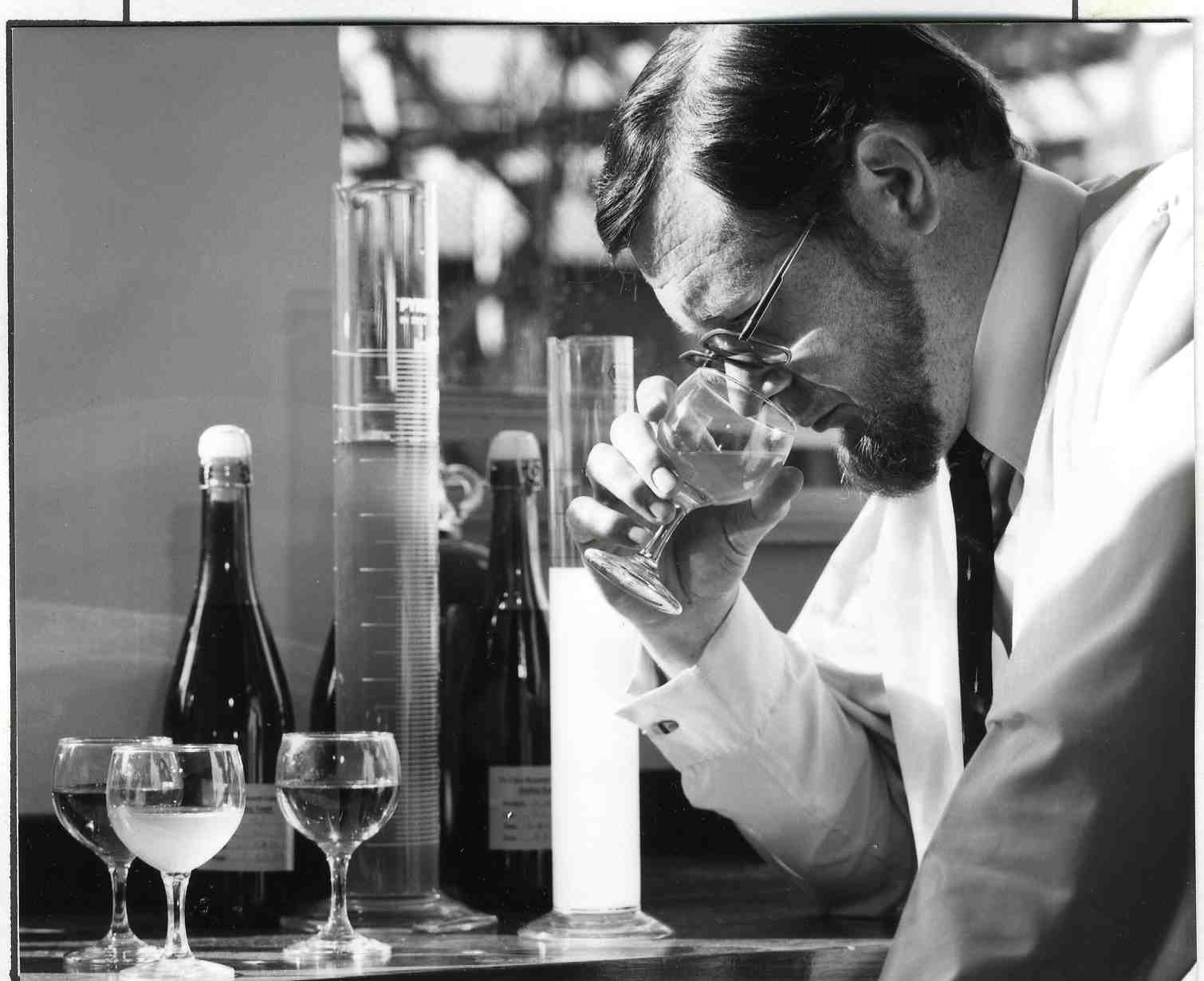

Cider in factories was made to a recipe, albeit on a huge scale. Juices were mixed to reach a desired flavour and alcoholic content under the guidance of the cider maker, helped by tests from the laboratory and a board of in house and random tasters. New recipes were constantly being devised and worked up into a product, most of these failed, only a few made it through and became successful winners.

"We are forever looking at ways at bringing out new products, trying to keep ahead of the market, new labels, new styles of cider. … We have a fortnightly meeting and anybody can bring up ideas. Certain products we forecast, that will be the in thing for the next couple of years, its surprising how quickly things do age. Some never age, they are the good ones. ... The product development team comprises Production, Marketing and Sales, if necessary we do market research, but we haven’t had to do much. We get a designer in, and put our ideas to them, it’s a mixture of them and us. There are many failures, many failures. Anybody who says they haven’t had any isn’t telling the truth."

Tim Weston, Company Director, Westons Cider

"The main task was to plan. I would have ten or fifteen samples, and the analysis of all of these, blended on paper with calculations of what the alcohol and acid levels would be. You have to get a balance between the acid and tannins, the tannins and acids give it the instringency, and you want that, and the alcohol gives it some body and flavour. We would do the original tasting, and then it went to the panel. The panel would consist of chemists, some management and one or two guys off the production floor, a very broad panel. They would all taste it. I would go in there and say "this is what you’ve got, gentleman", "this is what we are trying to do". I would say "I suggest is we start off with 7% or 8% of this in the total blend" and I would either do the blend there myself, in miniature on the table or it would have been done beforehand by the chemists. They would taste them, the ones they didn’t like would go out. This was a very important part, it was what Joe Public was going to have. The panel tastings in the winter time, would be every six weeks, but in the summer it would be almost weekly, because of the volumes that were going through".

Cedric Olive, Chief Cider Maker, Bulmers

Packaging was and is a very important part of the process. For much of the 19th and 20th century it was largely done by hand, but tasks were divided up and huge numbers could be processed in a day.

"My first job (in 1963) was sighting bottles. In those days it was all man handled, there was nothing automatic. The empty bottles were fed in at the back of a machine, they came to the washer and were taken out by hand, put on a track and you sighted them. You were looking to see if there were flaws in the bottles or any foreign bodies because bottles were all re-used then. They went onto the filler. The one that was working the filler put the stoppers in because, they were old fashioned stoppers then, then they went on down to a machine which labelled them. There was someone working another machine and put the bottles under what was called a strap labeller and they were pushed to someone who packed them into wooden cases and then they were sent down onto what was called the deck. There they were stacked, ready for the lorries."

Doreen Pocknell, Westons, Much Marcle

"When I first started at 15 in 1959, I worked in the packing room which is where the (Cider) museum is now. We used to do special orders we used to label, we had a labeller and put on by hand, one side to the other and into the crates on one side. There were five girls rubbing down, they used to foil, and rub the foils down, put them into crates, then we had to polish, and then they were rolled into pink or blue paper and put into crates and then there was a man he used to push the crates down on some rollers and use this little gadget that used to tighten the wires up and they’d go out onto a pallet and taken away."

Maureen Morris, Bulmers

Ten thousand bottles a day could be decorated in this way.

When Bulmers opened the new bottling line at Moorfields in 1957 it boasted it was the largest and most advanced in the world. It was capable of filling 1500 dozen (18,000) half pint bottles and 800 dozen flagons in an hour.

"When I was 17 I moved onto the bottling line for flagons. I thought ‘grief, these huge machines, huge’, I thought ‘have I done the right thing’. When I did de-crating I thought I’m never going to get this job, but I did. I loved it. It was keeping up on the line, I think we did about 300 or 400 an hour and you had to keep going. The crates would come down on chains, you had the wooden crates, sometimes with lids, you had to lift them up, take the bottles out two at a time onto the rollers to be washed, and the crate would go on, you had to take the broken crates off. You had buttons to stop the conveyor but you kept it going if you could. You got faster with practice. If bottles came down the wrong way round you would lift them out, toss them and put them the right way, you got good at that."

Maureen Morris, Bulmers

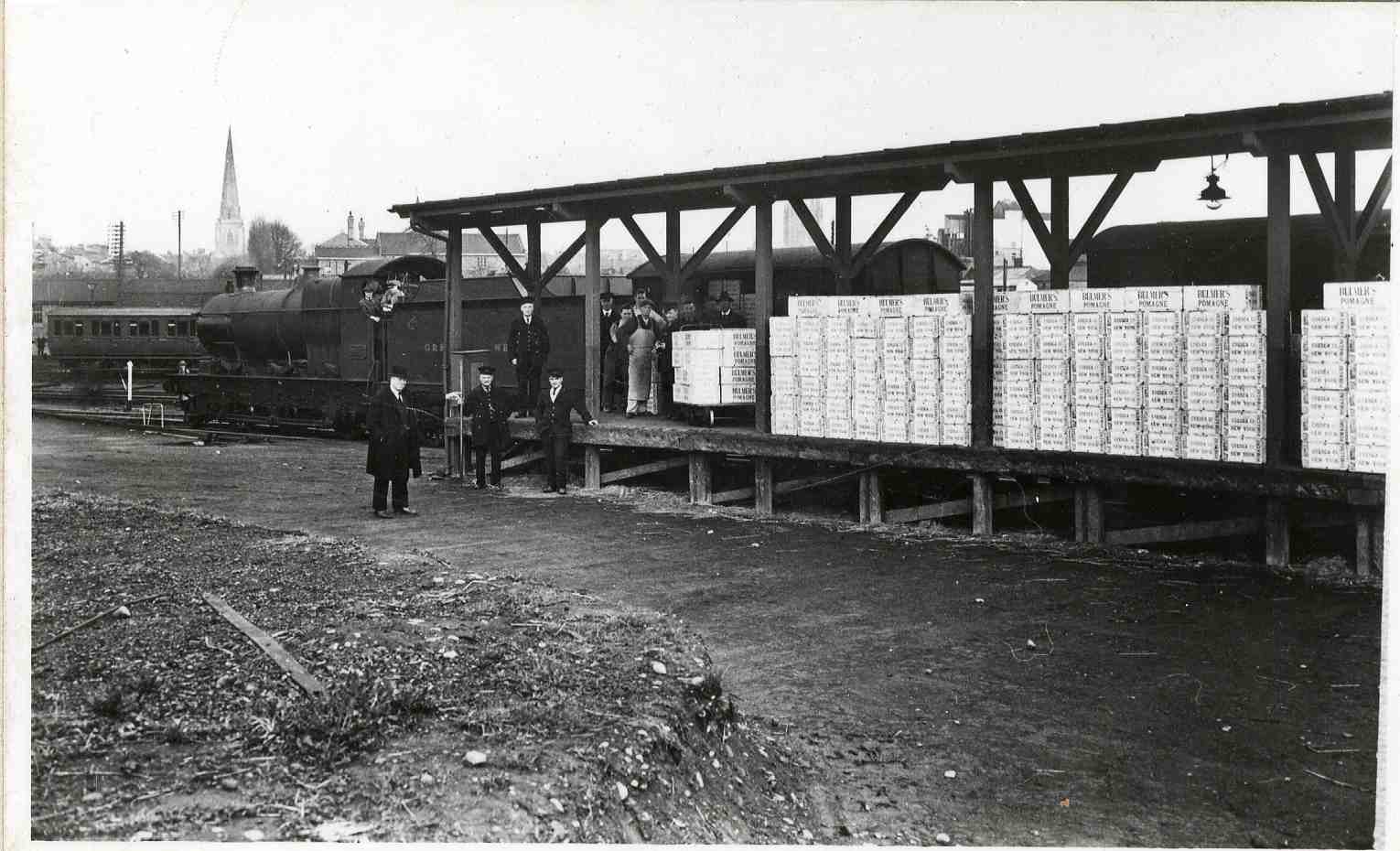

Distribution was a whole department to itself. Until the 1960s a lot went by train, the Bulmers factory for example was located adjacent to Barton sidings and station.

The first consignment of cider on its way to America by train, at the end of prohibition in 1933

At one time Bulmers, the largest factory in Herefordshire, had a fleet of 170 vehicles and 112 drivers. They had depots in all the major cities in the country and the depots themselves could employ up to 30 people. Here John Fellowes describes his work driving from 1955 to 1975 and working in the garages between 1975 and 1995.

"When you initially start driving at Bulmers you delivered radials, that was local deliveries. You didn’t have to load, they loaded in the factory, but you took them and unloaded them there. We used to put 488 dozen, quart bottles in the early days. We used to deliver to all the pubs and off licence that the breweries didn’t deliver to. You always had a drink after delivering, no such thing as drink and drive. I went on the tankers in 1957/58. I preferred the long distance, it was easier, easier than putting crates down cellars. The tankers were going to places bottling cider, there were quite a lot of bottling places in those days. And then there was the pectin, going to the jam factories. The pectin was delivered in tankers. I used to go as far as Montrose and Dundee in Scotland, we went to every jam factory in the country. In my days lorries could only do 32 m.p.h flat out. When I went to Montrose if you were on your own, it would take five days. Some times they put two drivers on, it extended the working day and you could do it in four days then. We were taking 3,000 gallons to Montrose. You stayed wherever you could get, places where lorry drivers used to stay. Some were good, some not very good. In a place like Newcastle you’d find perhaps a dozen for fifteen places you knew did transport. Because a lot of these B and Bs don’t want to get up in the morning, these places catered for early morning starts, they knew them in the office and they used to book them up for you.

We had good garage staff. They’d be serviced every month, inspected every fortnight. If there was something wrong with it, it would be done by the next morning. The mechanics worked on three shifts, one shift worked through the night. You’d come back empty but if it was London, you’d go over to Tate and Lyles and bring sugar back. We didn’t phone back to base, there was nobody to tell you what to do once you went out in the yard. There were 60 or 80 drivers, including 20 lorry drivers mates.

When I was in maintenance from 1975 we were working in two shifts, 6 to 2, 2 to 10 and swapping every week. I did a lot of lorry painting, I’d done some in the air force, I did new lorry spraying. They painted them in the Bulmer colours, green and red, later they changed the chassis into brown and did away with the red. There were about 30 people in the garage. They bought brand new lorries, when I first started there was a lot of Leyland's and Fodens, and then they went over completely to Fodens (Sandbach) for all the big lorries, then to ERFs at Sandbach and then to Volvos. The transport directors decided what types. I repaired them, the body work, curtains on the trailers, things like that. We painted them every four or five years. In the later days they didn’t bother, they bought new. They were working day and night and they wore out quickly. They were probably about the best fleet of maintenance you could come across."

John Fellowes, Bulmers

People generally wanted to work in the factory, for many it was a better alternative to farm work, the pay was more, you were inside, and people enjoyed the camaraderie and being part of a recognised organisation.

It is important not to underestimate the skill involved in factory work. You had to be fast, accurate and a good team member. Here is Trevor Watkins talking about women packaging when he was a young laboratory assistant in the late 1940s and ‘wet behind the ears’.

"They would have the tabs on a paste board above the bottling line and they had to put an individual tab on an individual bottle, they were so quick … they came from farm labourer stock, but the farm labourer was a highly skilled job. Many of them came from hard jobs, outdoor in all weathers and earning £2.00 a week. At Bulmers you were getting £2 10s (£2.50) and working under cover, it was better."

And here is Maureen Morris talking about packing the pomagne cider.

"You’d get the bottle out of the crate, you put a triangular shape foil round the neck of the bottle and cover the cork, you’d rub it down with a piece of sacking, then you’d put the neck band on, you’d wipe them down and then it would go to someone else. If you were really good at it you’d do quite a few in a minute. You had to have it really properly done. Mr Howard used to come round, you had to have the bands on properly, no glue showing."

And Ben Emmett about working in the pectin factory:

"My first job was dropping first time filters. You had to close them off by hand. I expect the filter would be from here to that window with all plates and frames in, you drop all those and you had to shut all them off by hand with a big wheel to tie them tight. It was very hard work. To close the filter up you had to have three of you. One climbing up on top of the grill throwing yourself back and two more pulling the wheel up, it was a great big wheel. Once you closed it up which was hard work, if you had what we called a leak, where it wasn’t actually sealing, and you get boiling pomace blowing out to the side you had to open it up again and see which plate was leaking. You’d left a bit of pomace on the face like, that was all that caused that."

As with everything else, cider production changed as new machinery and products were invented, and jobs had to change too, everyone had to learn new things and adjust. People moved about the factory, into new jobs as the need arose. It was possible to work your way up as well, promotion was often within the company and many heads of departments started as general hands in production or packaging.

A striking thing you notice when talking to workers is the loyalty and camaradie people had with their firm, be it Westons, Bulmers, Evans whatever. Many people spent their entire working lives with the same company, and at the end felt satisfied that they had done something useful and worthwhile, and work had often been fun. The work ethic was strong, money was the driving force but the way to get it was through work and especially through overtime. Most people (but not all) were keen to do overtime and shift work which began in the1960s when demand increased, because you were paid more.

It is remarkable the long hours people worked. Ben Emmett worked for twelve years, seven days a week, often twelve hour days. The only time off was two weeks holiday and staff cricket and football matches at the weekend. Cedric Olive, chief cider maker during the cider making season, September to December, worked all the time:

"My hours were terrible, 24 hours a day I worked for about 20 years. Always on call, no fixed hours. I could go to work at 7.00 in the morning, very rare but on occasions I wouldn’t be home till 10.00 at night. If we had a major problem at the mill I wouldn’t be home till that time. There was no overtime. This is the honest truth. In 1968/1969 the operators on the factory floor in the mill were earning more money then I was because they were on overtime. My basic pay was £22/23 a week. Which wasn’t a bad wage, but for the hours I did it should have been £222 a week. Management didn’t get paid for overtime. It was a job finished."

People drank a lot of cider at the turn of the century, it is estimated that 55 million gallons were drunk in 1890 which declined to 21 million in 1920. Much more is sold today, the British drink more cider than anywhere else, about 6 million hectolitres a year, which is 132 million gallons a year. But then the population is both considerably larger and more wealthy than it was.

At the time of the famous book, the Herefordshire Pomona (1876-1885, on display in the Cider Museum), it was estimated that there were 30,000 acres of cider and perry orchards in Herefordshire. This is 12,145 ha or 6% of the county area. In the 1930s and early 1940s it had reduced to 4.5% with cider apples accounting for 60% of this, perry only 6% and dessert fruit the remaining 34%. Herefordshire produced one fifth of the cider fruit in England and Wales and one quarter the perry. This area has reduced today but there is still a robust demand for apples from Bulmers, Westons and smaller cider producers. There are hundreds of acres of orchards in the county.

Top of PageIn the 1920s Bulmers were dominant in the Midlands and Wales, Whiteways in London and the south and Gaymers in the east, north and Scotland. These firms maintained their dominance by buying out most of the smaller firms in the area.

Before 1930 Bulmers exported a considerable amount of cider to Ireland, at this time the duty was low. The cider factory W Magner of Tipperary managed to get an import duty of 1s gallon put on in the mid 1930s. Bulmers then bought 50% of Magners and increased production eventually to 2m gallons a year of cider and Cidona. In 1946 Bulmers bought the remaining 50% which was then called Bulmers Ltd Clonmel, Pectin Ltd Clonmel and Apple Products Ltd Clonmel. An episode followed that led to Bulmers losing this now successful business. Showerings were selling Babycham ‘with enormous success’. Bulmers brought out a brand in competition but were challenged in court by Showerings and lost the case. The lost case had particular repercussions in Ireland. Bulmers decided to sell the company. It was sold on to Guinness and Allied Breweries, parent company of Showerings. Showerings at the same time forced a price reduction in cider, to the detriment of Bulmers.

1945 the Cheltenham Brewery which sold cider made by the Gloucester Cider Company, the successor to Wickwar Cider Company, through its tied houses merged with Hereford and Tredegar Brewery Ltd to become Cheltenham and Hereford Brewery. In 1958 it merged with the Stroud Brewery Co and became the West Country Brewing Holdings Ltd with 1,275 tied houses. This was taken over by Whitbreads. Whitbreads sold the Gloucester Cider Co to Bulmers in 1958.

In 1982 they were the second largest producer of pectin in the world.

Bulmers took over Godwin’s in 1948. In 1956 it went into voluntary liquidation with a distribution to Bulmers of £28,375. The buildings at Holmer were used for storage only.

In 1959 Bulmers acquired the majority shareholding of the Gloucestershire Cider Co at Wickwar to stave off an amalgamation with Stroud Breweries who would then have controlled most of the pubs in a 40 mile radius of Hereford. Through this take over they obtained an interest in the Creed Valley Cider Co of Somerset.

In 1960 Bulmers bought from Webbs (Aberbeeg) Ltd the goodwill of William Evans and Co. Of its premises only the vat house was taken over, which was later sold in 1967 for £12,000 to Saunders Valve Co. This meant Bulmers’ cider would be on sale at all Webbs licensed premises. They expanded the pectin factory to incorporate the Evans pectin.

In 1965 they bought all the issued shares of the Tewkesbury Cider Co which gave it access to Ansell’s Brewery pubs.

In the mid 20th century The Bottlers' Year Book listed 64 commercial cider makers. They were all based in the orchard areas of the West Country and Kent. As you can see, several of these survive today, others were taken over and others went out of business

| CiderMaker | Town | County |

|---|---|---|

| Anglo Apple Mills Ltd | Shepton Mallet | Somerset |

| Arnold and Hancock Ltd | Wiveliscombe | Somerset |

| Ashford Valley Cyders Ltd | Ashford | Kent |

| Avalon Orchards Lt | Glastonbury | Somerset |

| Bentall Lloyd and Co Ltd | Totnes | Devon |

| Bodyguard Cyder Co Ltd | Smarden | Kent |

| Boulton J and Sons Ltd | Hereford | Herefordshire |

| Bowden and Coombe Ltd | Totnes | Devon |

| Brutton, Mitchell Toms Ltd | Yeovil | Somerset |

| Bulmer H P and Co Ltd | Hereford | Herefordshire |

| Carr and Quick Ltd | Exeter | Devon |

| Cheddar Valley Cyder Co Ltd | Cheddar | Somerset |

| Coate, R N and Co Ltd | Nailsea | Somerset |

| Cotswold Cider Co | Gloucester | Gloucestershire |

| Creedy Valley Cider Co | Crediton | Devon |

| Dartington Orchards Ltd | Dartington | Devon |

| Dorset Farm Cider Makers' Federation Ltdq | Bridport | Dorset |

| Dowdens Ltd | Newton Abbot | Devon |

| Dyke E H and Son | Wincanton | Somerset |

| Evans, Wm and Co (Hereford and Devon) | Hereford | Herefordshire |

| Ferris Ellis and Co | Dawlish | Devon |

| Garden of England Cyder Co Ltd | Hawkhurst | Kent |

| Gaymer W and Son Ltd | Attleborough | Norfolk |

| Gloucestershire Cider Co Ltd | Wickwar | Gloucestershire |

| Goldwell Farms Ltd | East Malling | Kent |

| Grew, James and Co Ltd | Portadown | Northern Ireland |

| Hamberidge Brewery Ltd | Curry Rivel | Somerset |

| Harley Bros (Fair Oak) Ltd | Eastleigh | Hants |

| Hinge Fruit Products Ltd (Great Clayne Cider) | Gravesend | Kent |

| Horrell and Son Ltd, Stoke Vale Cider Factory | Exeter | Devon |

| Ixworth Cider Co Ltd | Bury St Edmunds | Suffolk |

| Knight, H (Huntley) Ltd | Huntley | Gloucestershire |

| Lorna Doone Cider Vintage Ltd | Langport | Somerset |

| Magna Cider Co Ltd | Marston Magna | Somerset |

| Milverton Cider Co Ltd | Milverton | Somerset |

| Newdigate Cider Co Ltd | Newdigate | Surrey |

| Orchard Gold Vintage Cyder | Smarden | Kent |

| Pope and Sons | Staplehurst | Kent |

| Pullin A I | Berkeley | Gloucestershire |

| Pullin Bros | Bristol | Somerset |

| Quantock Vale Cider Co Ltd | Bridgwater | Somerset |

| Rea F H | Wotton-under-Edge | Gloucestershire |

| Robbins W S and Son | Stroud | Somerset |

| Robins C and Co, Crown Cider Works | Tenbury Wells | Worcestershire |

| Rogers B Ltd, Sunshine Cider Mills | Chard | Somerset |

| Rout L F and Co Lt | Banham | Norfolk |

| Severn Vale Cider Co Ltd | Tewkesbury | Gloucestershire |

| Sheppy, S J and Son | Taunton | Somerset |

| Showerings Ltd | Shepton Mallet | Somerset |

| Symonds W R | Stoke Lacy | Herefordshire |

| Symons John and Co Ltd | Totnes | Devon |

| Taunton Cider Co Ltd | Norton Fitzwareen | Somerset |

| Teign Cider Co Ltd | Newton Abbot | Devon |

| Tewkesbury Cider Co Ltd | Fiddington | Gloucestershire |

| Turner W M | Pinhoe | Devon |

| Wakins' Pomona Cider Co | Hereford | Herefordshire |

| Wellington and Hallett | Bradninch S O | Devon |

| Weston H and Son | Much Marcle | Herefordshire |

| Whiteways Cyder Co Ltd | Whimple | Devon |

| Willets S | Blakeney | Gloucestershire |

| Williams Bros | Blackwell | Somerset |

| Wisbech Cyder Col Ltd | Terrington St John | Norfolk |

| Wright S and Co (Walkern) Ltd | Walkern | Herts |

| Yeomans Bros | Leominster | Herefordshire |

Firms in the Herefordshire area

Top of PageMost of the smaller cider firms were bought by Bulmers during the 20th century. Generally their equipment was taken, some of the staff made redundant and others transferred to Bulmers and the factory closed down.

Their letterhead states, 'Sole Makers of CIDER ROYAL AND PRIORY PERRY, Productions par excellence, Cider and Perry Merchants, Mills and Stores, Leominster. They were trading, selling bottling cider by cask (for bottling) with small oval labels if required in and around 1924.

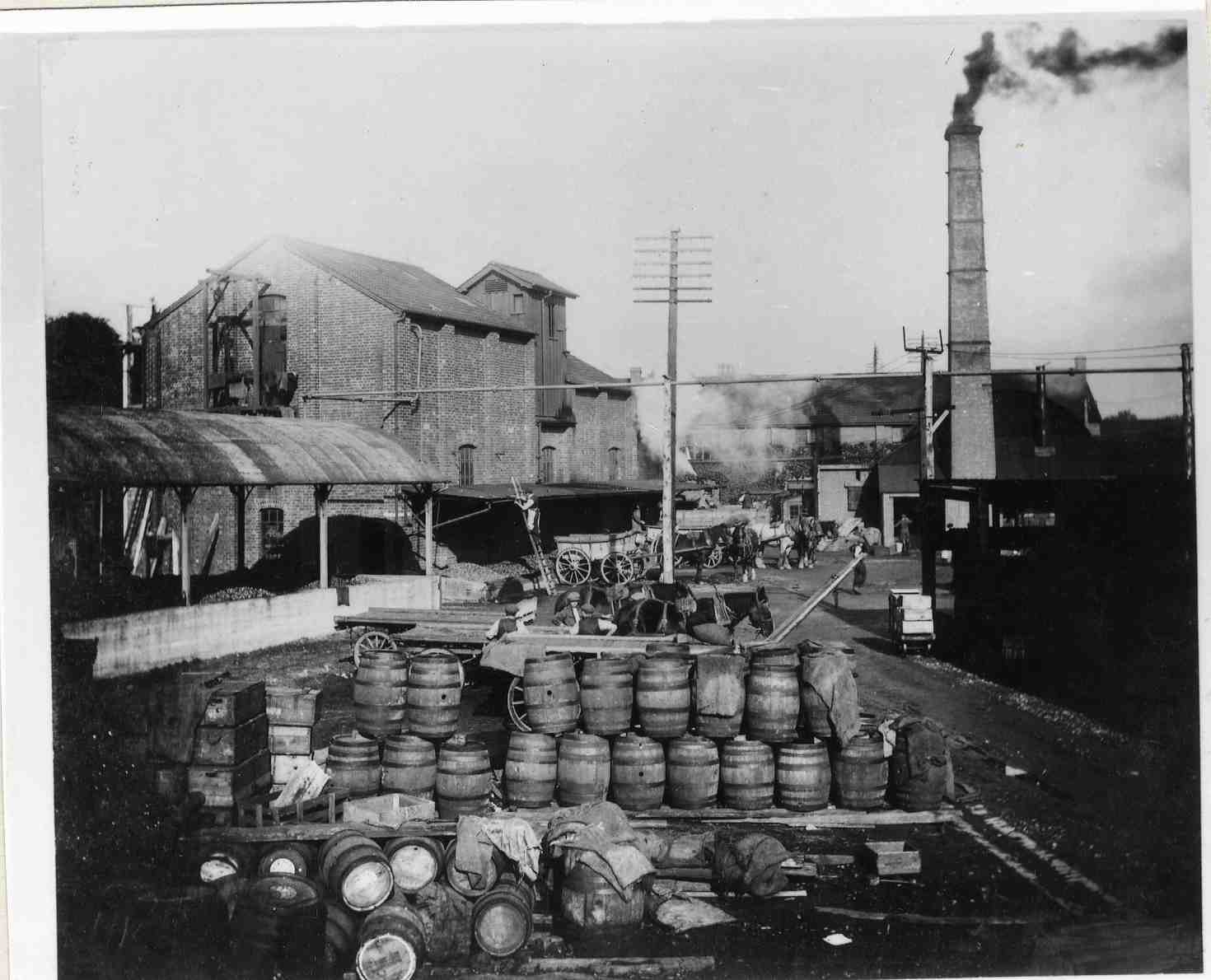

Godwins Jubilee Cider Works was established at Holmer by Henry Godwin in 1898. Steam powered it could make 20 hogsheads (a hogshead is 64 gallons, though in Herefordshire it can mean 100 gallons) a day. The cellar held 60,000 bottles of cider and perry. It was bought by Bulmers in 1948 and wound up as a company in 1962. The site was sold to Henry Wiggins and Co.

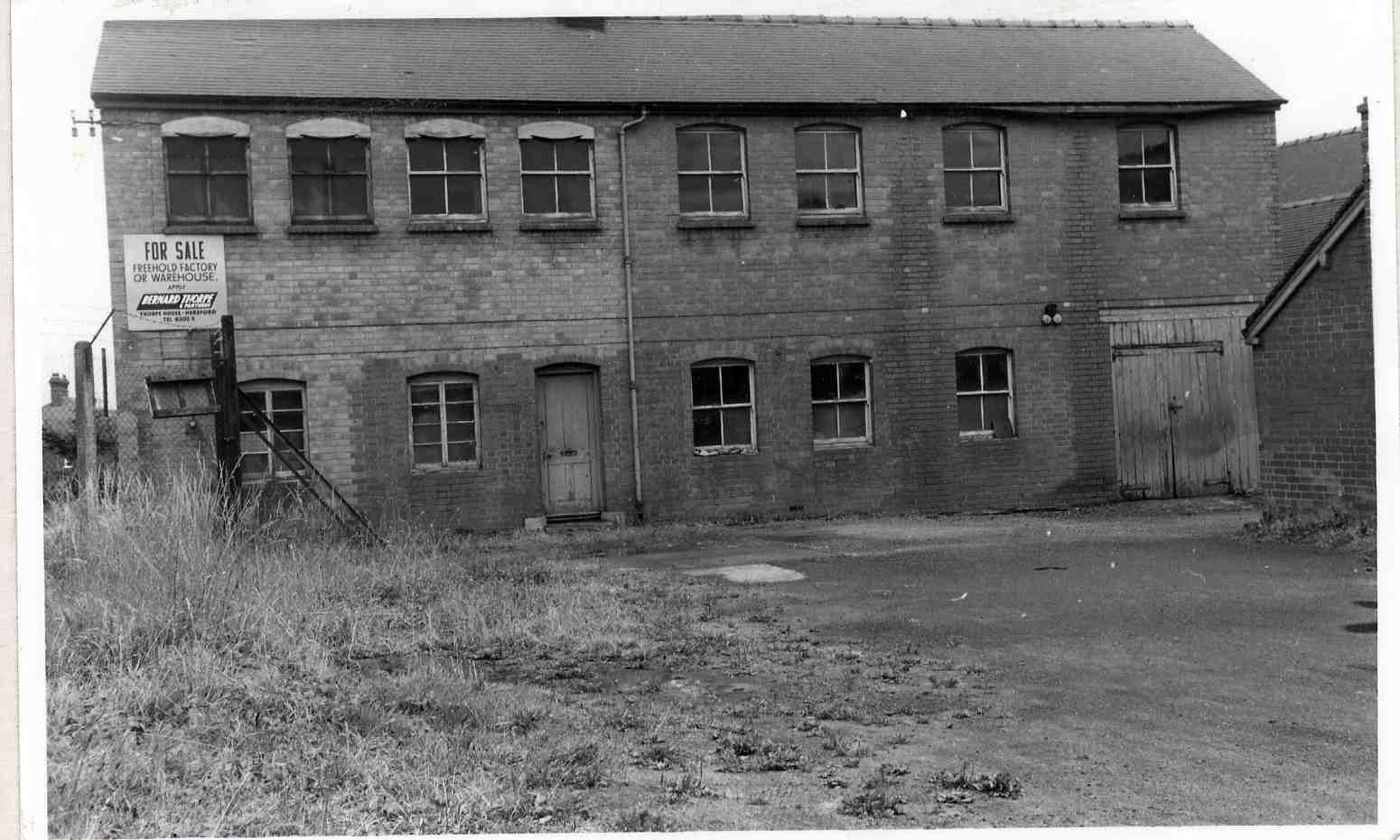

Godwins factory, just before demolition

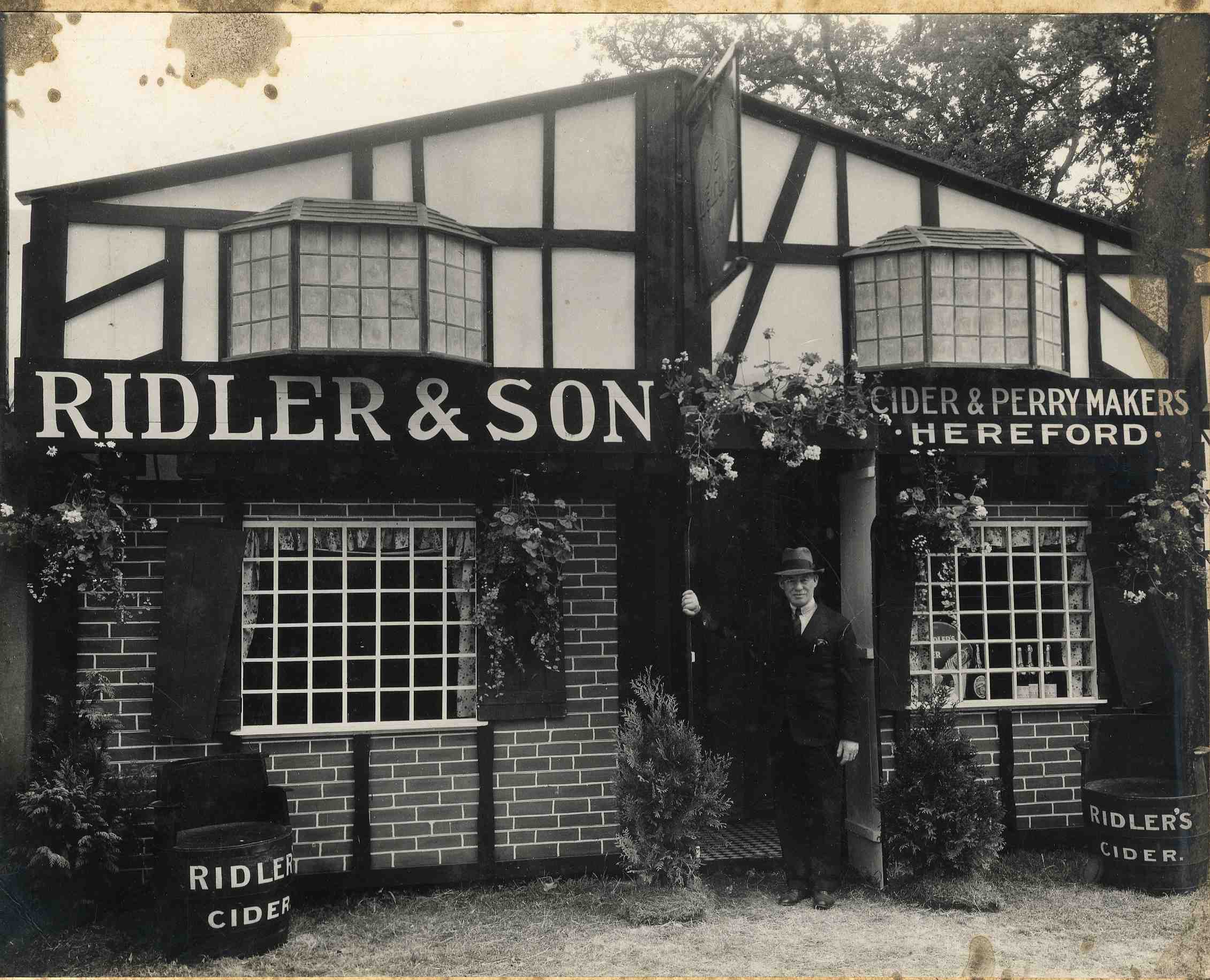

Ridlers of Clehonger 1870

Ridlers cider developed out of a farming business at Clehonger. By 1905 the establishment was sufficiently big to be called a ‘farmer and cider maker’. The business continued through the 1930s and 1940s and was eventually bought by Evans.

W M Evans of Widemarsh Common Top of Page

This firm was established 1850 as a Cider Merchant at 9 Blue School Street, Hereford. It was moderately successful and sold in 1884 to William Chave, Chemist, for his sons. By 1891 the business had moved to larger premises in Widemarsh Common and was now termed Cider and Perry Makers. In 1900 it bought a Boomer and Boschert Press from New York and soon built another factory in Devon. By 1934 Evans were the makers of Golden Pippin Cider and, since 1917, Elpex apple pectin sold as ‘Fermagel’ which was used to set jams. This became the chief product. During the War pectin was controlled and sold by the Ministry of Food and all the pectin produced in Great Britain to 1950 was made in Hereford. In 1946 Evans was sold to the brewers Webbs of Aberbeeg and in 1960 Bulmers took over the firm. The sale included 558,000 gallons of cider storage and the pectin factory which it transferred to its own recently established pectin factory at Ryelands.

Bosley & Co, Lyde, Hereford

The Bosely family had grocery business interests in Herefordshire, two brothers dealt in hops, using the Green Dragon, Hereford as a base in the 1860s. In the 1890s Bosley & Co, Cider Makers based at Lye, Hereford was selling hogsheads of single variety and mixed fruit cider to wholesalers for onward sale.

Joseph Davies, Venn's Green, Marden, Hereford

Produced bottled and casked cider, prize winner in the late 1870s/early 1880s, sold to William Pulling for onward sale.

Henry Weston of Much Marcle 1880 Top of Page

The firm was begun by Henry Weston who was a tenant farmer of Homme House Estate based at the Bounds farm. He was encouraged by Radcliffe Cooke, one time MP and cider champion who lived at nearby Hellens house to make cider. He invested in machinery and began to sell cider through merchants. His vision was always to make quality cider from single variety apples. By 1906 Westons pressing house was capable of dealing with 100 tons of fruit in 24 hours. By 1916 Westons were the suppliers of cider and perry to the House of Commons, the drink being transported on the railway from Dymock. Westons have grown, expanding both output (about 3 million gallons a year) and the enterprise which now has a thriving visitor market. But it is still a family firm, employing local people and it was only in the early 2000s that a Bucher press replaced the traditional flat bed presses.

Westons, Much Marcle, Doreen Pocknell beside a flat bed press, now in the Museum

Bonner and Durrant, Holmer

This firm was present in 1913, but by 1934 it was no longer listed. It was possibly taken over by Watkins Pomona Co.

Watkins Pomona Co Ltd, Withington, Near Hereford

The firm began in 1881, in 1903 it went into voluntary liquidation, selling the business of plant and equipment including 4,000 casks and 1,000 storage casks, 450 hogsheads of cider and 700 dozen bottles of cider and perry and 1000 empty bottles. A railway sidings connected the works with Withington Station. It was offered for sale and the purchaser could take the £3200 book debts with the sale, if they so wanted.

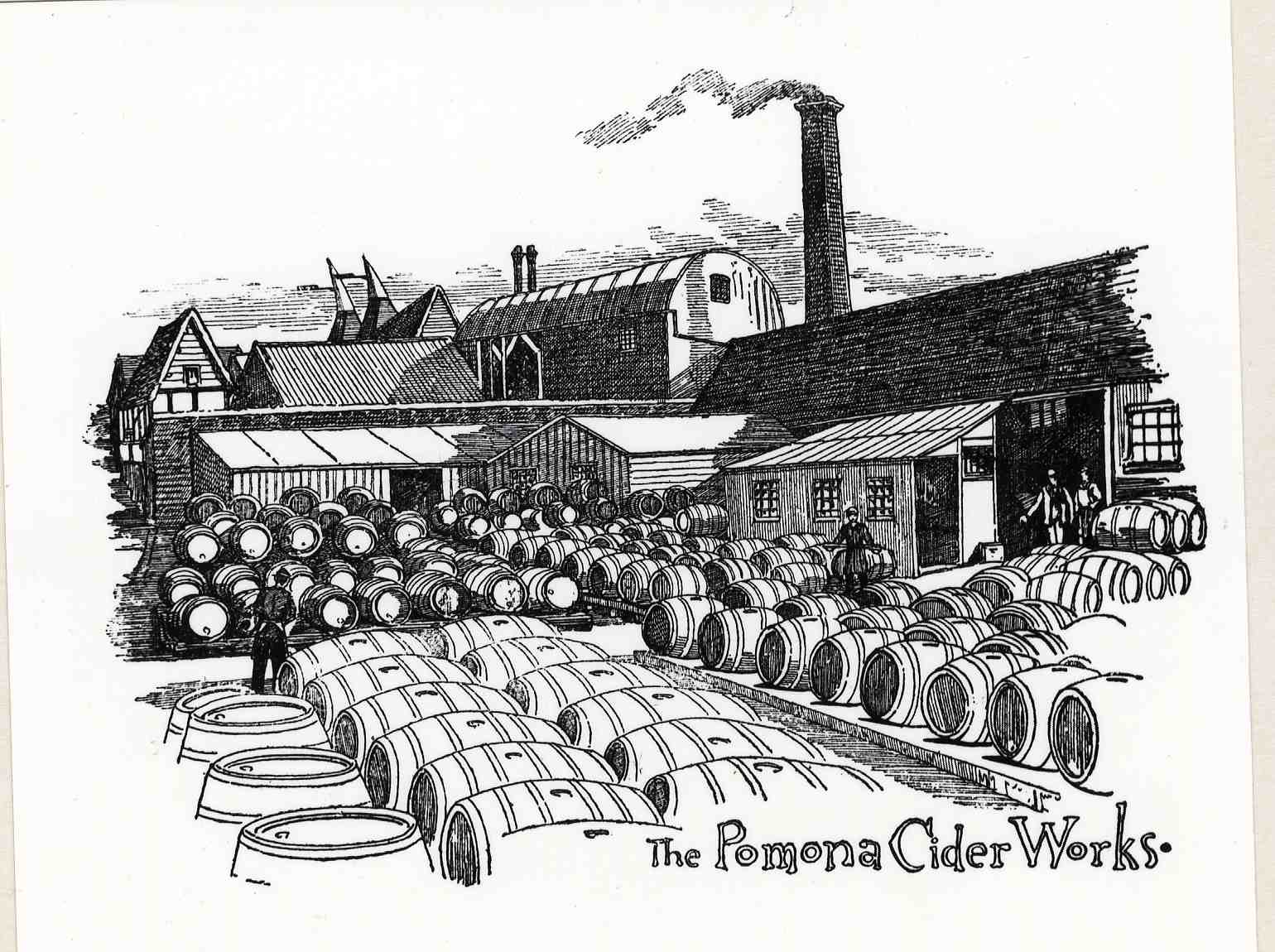

Watkins Pomona Co, Holmer Top of Page

This firm emerged in 1934, and continued into the 1950s.

Watkins Pomona Works, Holmer

Yeomans, Leominster

This firm emerged in the 1930s as a cider and perry maker able to supply small bottles and casks of any size. It continued into the 1950s.

Symonds began in 1727 at Stoke Lacy near Bromyard in Herefordshire. Its most famous ciders were Scrumpy Jack and 1727. At its biggest in the 1990s it employed 40 people, processed 6,000 tons of apples from neighbouring orchards and made over a million gallons of cider a year. In 1984 it was taken over by Greenall and Whitley which in turn was taken over by Bulmers in 1989. In 1990 it was described as a subsidiary of Bulmers called Symonds Cider and English Wine Company. In this year Symonds bought Frampton Village Cider of Gloucestershire moved FVC production to Bulmers and the Stoke Lacy site. The Stoke Lacy plant itself was closed in 2000 and the buildings bought and converted by the Wye Valley Brewery in 2001.

Symonds Factory

Fred Bulmer describes the beginning of the Bulmers factory, in a charming booklet called ‘Early Days of Cider Making’. He and his brother (H P or Percy Bulmer) were young men, sons of a gentleman vicar. Fred was Cambridge educated but Percy, due to ill health, had ‘no Education at all’ and it was he who began the cider business, joined one year later by Fred. In the first year of their enterprise, 1887, Percy produced 4,000 gallons of cider using traditional methods. The brothers became ‘whole time workers’, working round the clock. There were no cider making machines to speed the process up, so they invented them. With the help of an engineering friend the brothers innovated, they also imported a mill and press from France where production was more advanced, and in 1892 put in hydraulic pumps and two more presses. By 1894 they were selling £7558 of cider a year, 48 times more than the first year of their partnership in 1888. They also had a workforce. Bulmers only produced bottled cider in the early years and in 1898, just 11 years on from their first year, the bottling line employed 37 women.

Early days at the Bulmers Factory, Ryelands Street

Bulmers grew and grew. By 1919 there were 2 acres of cellaring below ground and they were selling 80,000 gallons p.a. which made a profit of £9,000. In 1937 as much as 20,000 tons could be pressed during the season September to December.

Between 1948 and 1960 turn over increased from £1,604,000 to £3,008,000. In 1957 a new bottling hall was erected at end of Plough Lane and by 1964 most bottling had been transferred there.

In 1970, in response to a cash flow crises brought on by investment in the company and high death duties on two family members, the decision was made to go public. The Bulmer family retained 65% of the shares.

In 1970 there were nine directors, four of whom were Bulmer’s family. The turnover was nearly £11m and they employed 1,817 people. Nearly 85,000 apple trees were planted in an attempt to keep ahead of demand and the orchards were producing 15,000 tons of apples a year. Output was over 100,000 gallons a day and their modern flagon bottling line could fill 12,000 bottles and hour. They had 60% of the £25m market (£15m). In 1985 the board had been divided into executive and non executive directors, 12 in all, four of whom were Bulmer’s family. By this time 35,000 tons of apples were being pressed a year. The record day was 1982 when the company pressed just over 1,000 tonnes in a day. The group produced several drinks including cider and had overseas operations. The total turnover was £138m and the profit £17m.

In 2003 Bulmers got into financial difficulties due to over investment abroad. The firm was taken over by Scottish and Newcastle. In 2008 Scottish and Newcastle were taken over by Heineken who now run the Bulmer's cider business. Fruit processing (crushing the apples) has moved from the Bulmers site in Plough Lane, Hereford to Universal Beverages Ltd (UBL), Ledbury, also owned by Heineken. Some fermentation, processing and bottling is also done at this site but the huge majority of production is still carried out at the Plough Lane site in Hereford. The fruit concentrate is taken into the factory here by tanker and processed into their leading brands such as Strongbow and Woodpecker employing around 250 people and producing over 3 million hectolitres a year (68 million gallons), about half UK total output. Bulmers also runs a bouyant Fruit Office employing 30 staff, managing 10,000 acres of orchard, about a quarter of which is company owned, the remaining three quarters is on long term contract to individual growers.

Bulmers early 20th century Bulmers 2006